The Reactive Engine

[Kay 69] Ph.D. thesis by Alan C. Kay, 1969 at the University of Utah

microfish – University of Hamburg M420

on this page: an excerpt

From: Alan Kay

Date: Mon, 13 Nov 2000 08:07:34 -0800

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abstract

- I a Preface

- b Reading Grade

- II Part A: The Basic Dialogue

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A Simple Interactive Language Interpreter

- 3 The FLEX Language

- a Translation

- b Deferment and Coercions

- c Abstraction and Attributes

- d Elaboration

- e Mapping

- f User Interaction

- g Modeling

- h An NC Language Proposal and Realization

- b Deferment and Coercions

- 2 A Simple Interactive Language Interpreter

- III Part B: Physical Considerations

- 4 The Pragmatic Environment

- 5 Segments and Processes

- 6 Memory Systems

- a Mapping

- i Contiguous Mapping

- ii Paged Segments

- iii Multi-level Schemes

- ii Paged Segments

- b Secondary Memory

- i Swapping

- ii The Disk as a Serial “Associative Memory”

- c An Associativeley Mapped LSI Memory

- i Contiguous Mapping

- 7 Algorithmic Processing

- 8 The Display Processor

- 9 Input and Output

- 10 Multi Machine Configurations

- 5 Segments and Processes

- IV Implementations to Date

- V Appendix A. The FLEX Handbook

- References

- Vita

- Abstract

Acknowledgements

Abstract

The design of machines which can participate in an interactive dialogue is the main topic of this thesis. To do this successfully, a language processor and a more general memory system will be incorporated as the lowest level of the hardware.

A richer level kernel language, FLEX, which is comprehensive enough to provide the basic dialogue, extend itself into more desirable forms, and describe other languages, yet is concise enough to be implemented directly as a hardware processor, is developed.

Several models of abstract interpreters for this reactive system, starting with a very simple textual model, are then discussed, followed by hardware representations of the schemes.

These considerations lead to the design and implementation of the “FLEX machine”, a personal, reactive, minicomputer which communicates in text and pictures by means of keyboard, line-drawing CRT, and tablet.

I a Preface

b Reading Grade

II Part A: The Basic Dialogue

1 Introduction

It is not the purpose of this book to determine why human beings build machines, nor is it to describe how. Yet a certain amount of metaphysics may creep into the discussion from time to time, since any investigation into the design of devices which are actually used by people must of necessity try to guess what the class of potential users will want. Of course, they do not know themselves if their needs are potentially interesting, and it is useless to poll the remainder (as previous experiments have shown) for they exhibit the well-known “committee syndrome”: “… the only form of life with ten bellies and no brain.”

A good class project for undergraduates who have not become too tainted with either the commercial or research computing milieu, is to have them design a computer system for a “think tank” such as RAND or the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. It is delightfully nebulous question, since they quickly realize it will be impossible for them to even discover what the majority of the thinkers are doing. Indeed, many of the researchers will not know themselves or be able to articulate that state of mind of “just feeling around”. It is at this point that a wide philosophical division appears in the students. Almost all of them agree that there is really nothing that they can do for the scientists. The more engineering-minded of the students, seeing no hard and fast solution, stop there. The rest, who are somewhat more fanciful in their thoughts, say “…maybe ‘nothing’ is exactly the right thing to deliver, providing it is served up in the proper package”. They have articulated an important thought. Not being able to solve any one scientist’s problems, they nevertheless feel that they can provide tools in which the “thinker” can describe his own solutions and that these tools need not treat specifically any given area of discourse.

The latter group of students has come to look at a computing engine not as a device to solve differential equations, nor to process data in any given way, but rather as an abstraction of a well-defined universe which may resemble other well-known universes to any necessary degree. When viewed from this vantage point, it is seen that some models may be less interesting than the basic machine (payroll programs). Others may be more interesting (simulation of new designs, etc.). Finally, when they notice that the power of modeling can extend to simulate a communications network, an entirely new direction for providing a system is suggested.

While they may not know the jargon and models of an abstruse field, yet possibly enough in general of human communications is known for a meta-system to be created in which the specialist himself may describe the symbol system necessary to his work. In order for a tool such as this to be useful, several constraints must be true.

- The communications device must be as available (in every way) as a slide rule.

- The service must not be esoteric to use. (It must be learnable in private.)

- The transactions must inspire confidence. (“Kindness” should be an integral part.)

[…]

First Principles

Machines which do one thing only are boring, yet exert a terrible fascination. […]

It is well known that humans need to build a mental model of their environment before they can apprehend it in any way. Probably the two greatest discoveries to be made were the importance of position in a series of grunts, and that one grunt could abbreviate a series of grunts. Those two principles, called syntax (or form) and abstraction, are the essence of this work.

[…]

It was the discovery of Hopi that led Whorf to the conclusion that the way a group of people see, hear and think about things is constrained by their language, since that is actually the medium through which they build and manipulate their internal models of the world.

Noting these thoughts leads one to a sobering situation when contemplating the design of a system to represent the form (syntax) and the modelling (semantics) that is necessary to represent a universe (albeit a small one). […]

2 A Simple Interactive Language Interpreter

3 The FLEX Language

FLEX is an acronym for “Flexible Extendable”. It was first used to denote a very Euler-like language that was devised in the summer of 1967 to answer a need for a “higher level” system which could easily be interpreted by hardware. […]

There were several important differences [to ALGOL-58 and ALGOL-60], however. FLEX was always intended to be interactive. From the first, the hardware interpreter was to have a “scope” for graphical (as well as textual) output. As a generalized vehicle for modeling situations, there was a strong need for the ability to create logical “instances” as well as “copies” and to simulate running them concurrently. Neither ALGOL-60 nor Euler and its further generalizations cared to tackle these problems. An ALGOL-60 deviant, SIMULA made a notable attempt to describe concurrent processes, but was tremendously hampered by the statically-nested structure of ALGOL, which it adopted.

Structure of some kind (and control of it) was definitely needed. The initial delights of the strongly interactive languages JOSS and CAL have hidden edges to them. Any problem not involving reasonably simple arithmetic calculations quickly developed unlimited amounts of “hair”. While interactive conversation was pleasant, since it was transacted in the same language in which one programmed, there was a great lack of essential touches for a supposedly “kind” system. […] Although BASIC has a structure somewhat like FORTRAN, it is not really interactive, since the user transacts business in a simple “operating-system-like” manner, and the response is very much like a dedicated batch system.

Most other higher level, so called “interactive” systems were like TINT (a variant of ALGOL-60) in which the reactions with the system are very much like BASIC: The user is stuck out in a corner, viewing his world through a very narrow porthole.

A notable group of exceptions to all the previous systems are Interactive LISP […] and TRAC. Both are functionally oriented (one list, the other string), both talk to the user with one language, and both are “homoiconic” in that their internal and external representations are essentially the same. They both have the ability to dynamically create new functions which may then be elaborated at the users’s pleasure.

Their only great drawback is that programs written in them look like King Burniburiach’s letter to the Sumerians done in Babylonian cuniform! […]

[In FLEX] Files were subsumed by the ability to use the co-routine exit leave to log off the machine, thus preserving state until next log on. […]

FLEX in 1969

[…]

The summer of 1969 sees another FLEX (and another machine). The goals have not changed. The desire is still to design an interactive tool which can aid in the visualization and realization of provocative notions. It must be simple enough so that one does not have to become a systems programmer (one who understands the arcane rites) to use it. […] It must do more than just be able to realize computable functions; it has to be able to form the abstractions in which the user deals.

These goals have not been reached.

[…] However, the program to do the solution can be debugged with less tears than on other systems.

FLEX is an idea debugger and, as such, it is hoped that [it] is also an idea media.

a Translation

b Deferment and Coercions

c Abstraction and Attributes

d Elaboration

e Mapping

f User Interaction

Introduction

Admitting the user to the Machine

[note: same as in [Kay 68]]

When it is desired to allow a new user access to the machine, a process is created and named with his password. This process will not terminate during the period that he is allowed to use the machine. Most of the time it will lie passive on the secondary storage waiting to be reactivated which is simply done by the user typing in his password on the console.

The user’s process is activated, and he is now able to communicate with the machine through FLEX and the powerful editor which controls a free-running compiler that is translating everything that is entered through the keyboard to FLEX code. Since his process is also declared active, the pragmatic system will attempt to execute all produced code. This will appear to the user as though his commands at this lowest are being executed statement by statement.

By these means the user may entertain himself by performing calculations, editing text, generating new compilers, and generally going where his thoughts lead him. When he desires to cease running he simply types in a leave. This is the coroutine exit command and, since the routine which called him is the process scheduler itself, his process is passivated and the reentry point retained.

On the next day (or next week) when he again types in his password, his process is reactivated and control is passed to the reentry point; he is where he was the last time on the machine. This is why files (and file handling systems) are unnecessary on the FLEX machine. Any declaration he may have made (and possibly stored data in) have been saved to be used again.

Scope of the user

[note: same as in [Kay 68]]

The user at the console is considered to be inside a process description which in turn is interior to the FLEX system and environment. This concept of system globality fits well the FLEX philosophy and provides a convenient means of allowing the user access to entities such as the FLEX language tables themselves, reserved identifiers whose meaning he may wish to redefine, etc.

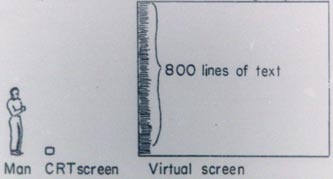

Virtual Screens

One other interesting ability of the display systems is the use of virtual screens. They may be thought of as rather large “bulletin boards” on which things may be tacked up.

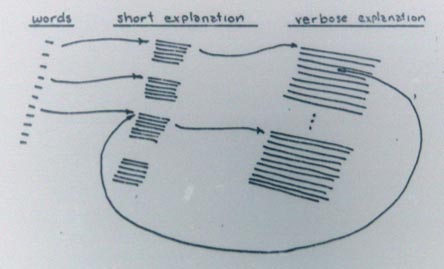

Fig. p.129

Fig. p.129

The screens are 16384 x 16384 points, compared to the output CRT’s 1024 x 1024. However, the windowing hardware allows any rectangular area of the virtual screen to be mapped to any rectangular area on the actual viewplate, so a v. screen is simply a high resolution place in which to draw. It should be no surprise to find out that text strings are already implicitly mapped to v. screens. About 800 lines can be tacked onto one side.

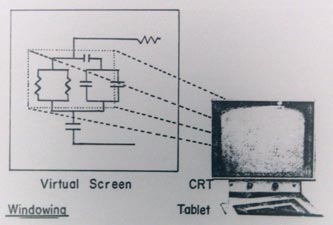

Fig. p.130

Fig. p.130

The portion of the display inside the windowed area is only what is transmitted to the CRT. A clipper is used to find the intersection of lines with the window boundaries. Any number of v. screens, windows and viewports may be superimposed.

The IO Facility

[…] keyboards, tablets and stylus, and vector-drawing scope.

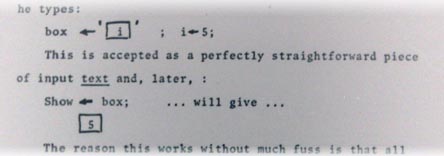

The default base has the stylus and both keyboards connected to the same input stream so that drawings can be directly entered in place of text. This is handy when no great precision of coordinates is needed. Suppose he just wishes to draw a box with a number inside of it. Then he types:

Fig. p.131

Fig. p.131

The reason this works without much fuss is that all input motions of the stylus are one-dimensional, all outputs by the scope are one-dimensional also (one line at a time), The mapping into text is obvious. It also allows

Pointing

The coordinates of the stylus may be identified with a window for the purpose of pointing to constructions. “Hints” are automatically detected by the clipping hardware when “visible” lines are found. This will cause “user whens” to function, most likely.

g Modeling

[…]

being able to draw in examples of graphics is … tremendously useful as it precludes having to use functions like plot line, etc., except where one has to be precise. […]

h An NC Language Proposal and Realization

[NC for numerically-controlled tool; later called CNC machines]

II. The Problem

A good NC language should at least include the following characteristics:

[…]

10. A parts program in this system is a “cartoon strip” consisting of a number of sequential frames. Each frame contains a picture of the piece, an indicated path for the tool, and textual notes giving constraints (tolerances, etc.) and explanations. It is in this form that a parts programmer plans his program and, because of the interactive and graphical nature of the FLEX terminal, it is possible to allow these plans to actually be the program – this eliminating paper, rough sketches, etc., completely.

[…]

Using the system

The designer (or parts programmer) sits down at the desk and joins the FLEX machine. He is automatically connected and enters the NC system. The first thing that is displayed is the top level of his own personal dictionary. He may choose to peruse it (explained in the next section), or he may just recover his context from the previous session and continue where he left off.

Since all portions of the language system consist of pictures and text, his normal mode of operation is as follows:

When typing in extended text, he will have both hands on the keyboard, as on a normal typewriter, Whatever he types will be echoed in the screen and he will have complete ability to edit and amend his text. When typing is statements in the language the system will be interpreting as he goes, so that the system can do a number of desirable things.

- The system will immediately inform him of a statement that has been typed incorrectly. He will not have time to forget what he is doing before being informed of an error.

- The system can anticipate what he is doing, If there is a word “VECTOR” in the vocabulary, and it is the only one beginning with “V”, the system […] can echo back “ECTOR”, […]

For pictures, the user will have one hand in the stylus, the other at the five-finger keyboard for function codes. (Both right and left-handed people may use their strong hand for pointing.) Words cannot do justice to the speed of interaction that is possible after only five to ten hours of use on a system like this. It really has to be demonstrated.

The Dictionary

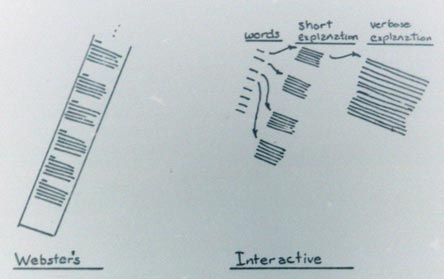

On an interactive system, this can be an exceedingly powerful tool. Webster’s Collegiate is very clumsy in comparison, since all of its information is basically at one level. To find a word, the user knows how it is spelled , yet he is forced to wade through all of the information (including explanations) to find his entry:

Fig. p. 157

Fig. p. 157

Webster‘s International is rarely used, because almost never does the interrogator want as much information as there is in a typical entry, On an interactive system, the computer is on hand to search, so that just the words can be presented. The desired word can now easily be found and pointed by the stylus. The display can then show a condensed explanation of just the word pointed to. If more information is needed, the stylus can again be used, to cause an expanded “encyclopedia” entry to be displayed. More tricks can be played. Suppose a word in the explanation is not understood. Does the user have to retreat to the top level to select the entry for the new word? Not if vocabulary words are linked together. Then the stylus can be used to point at the word in the explanation itself and its entry will then be displayed.

Fig. p. 158

Fig. p. 158

The user will return from each explanation in the reverse order in which he entered so that a perfectly natural way of using the dictionary develops. […]

In a sense, the vocabulary is not structured alphabetically only but is set up so that a minimum of perusal is necessary to find out something. (51)

Documentation

All knowledge there is of how to use the system will also be carried in the dictionary. Updates made by a programmer will thus be reflected automatically to all users. There will be a “mail” entry to leave messages, etc.

[…]

Dictionary Structure

Pictures and Objects

[Stereo images]

Stylus and Tables (p.161)

III Part B: Physical Considerations

4 The Pragmatic Environment

5 Segments and Processes

6 Memory Systems

a Mapping

i Contiguous Mapping

ii Paged Segments

iii Multi-level Schemes

b Secondary Memory

i Swapping

ii The Disk as a Serial “Associative Memory”

c An Associativeley Mapped LSI Memory

7 Algorithmic Processing

8 The Display Processor

9 Input and Output

10 Multi Machine Configurations

IV Implementations to Date

Two FLEX compilers (one with segments; the other without) were programmed in ALGOL on the UNIVAC 1108 system in February, 1986. Attempts were made to interface these programs with an interactive editor (also in ALGOL) and the graphics system (57). The failures were partially due to the inadequacies of ALGOL as a real-time and process language in general, and in particular, to the very real defects of the UNIVAC version of ALGOL-60.

The graphics display routines, character generator and editor ran for a year on an IBM 1130 computer with a “home-brew” interface. Unfortunately, the 1130 was straining to just act as a glorified display buffer, and none of the algorithmic routines were implemented.

In January, 1969, Dr. William Newman decided to use FLEX as the control language for the new PDP-20-PDP-9-UNIVAC display system. Henri Gouraud did the FLEX compiler in TREE-META (12) on the SRI (Engelbart) SDS-940. Dr. Newman and Scott Bennion programmed a mini-FLEX interpreter for the PDP-9, and it is able to serve four time-shared graphics users (58).

This system is now being brought up on the PDP-20 to act in tandem with the programs on the PDP-9. A complete implementation of FLEX on the PDP-10 is being contemplated, although the monitor is not quite right as to process creation and memory mapping.

That, unfortunately, is the crux upon which all implementations revolve. Hardware implementations need to be performed in order to get a reasonable initial memory system.

Several “mini computers” which allow user-defined micro code have been carefully studied as a possible object for hardware implementation. The Interdata Model IV seems to be much more suitable than the others that were examined. However (like the rest), it suffers because its micro organization is strongly prejudiced towards the IBM 360-like organization of the Model IV. Its main feature is that it has many hardware registers, which cover a multitude of other sins,

FLEX will only find its real home in the machine environment for which it was designed. This machine is currently being designed, and it is hoped that it will eventually be built.

The Experimental Display. An IBM 1130 (with disk) was used as the host […]

V Appendix A. The FLEX Handbook

References

Vita

–––––à propos

- full version of Alan Kay’s The Reactive Engine [1969]

- FLEX– A flexible extendable language, Alan Kay's M.Sc. thesis, 1968

- The Reactive Engine, Alan Kay's Ph.D. thesis, 1969

- A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages, Alan Kay, 1972

- Still Waiting for the Revolution: A Conversation with Alan Kay 2002

- Alan Kay Media Center

Incoming Links

- HCI Review of the Xerox Star

- ramanrao’s information flow: bio & history

- Wikipedia: Homoiconic

- Definition Of Homoiconic

- DigiBarn:The Newly Inspired Bushy Tree

- nooron: Reactive Engine

- Knowing and Doing: Alan Kay’s "The Reactive Engine", June 2007

- Wikipedia: TREE-META

- The best things and stuff of 2015

- A city is not a tree, Feb/2019