The development of Guide (cf. 2.1.9) starts in 1982 at the University of Kent. Peter Brown has a first version running on a workstation one year later. In 1984 the British company Office Workstations Ltd. (OWL) gets interested and releases a Macintosh version in 1986. Soon thereafter Guide is ported to IBM-PCs. Guide becomes the first popular commercial hypertext system. It shall be noted here that OWL offers also the option to import SGML files into Guide’s hypertext format.

Guide is probably the first hypertext system that has underlined hyperlinks.* * According to Harald Weinreich and Hartmut Obendorf in The Look of the Link – Concepts for the User Interface of Extended Hyperlinks [Weinreich et al. 2001], different text styles like bold and italic are also possible. It offers three different forms of links: jumps, pop-ups and replacements. The links look initially the same; yet they can be distinguished because the mouse cursor changes its shape accordingly.

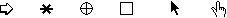

Fig. 2.9 Special mouse cursors indicate reference jumps, pop-up notes, open and close of inline replacements. Further to the right comes the standard Macintosh arrow cursor and the link cursor used by the Web browser Netscape Communicator.

Special mouse cursors indicate reference jumps, pop-up notes, open and close of inline replacements. Further to the right comes the standard Macintosh arrow cursor and the link cursor used by the Web browser Netscape Communicator.

Jumps are hyperlinks to other nodes, but they can also refer to locations within the same node. The mouse cursor changes to an arrow. Today’s browser use a pointing forefinger for this purpose. Pop-up links display a tiny extra window as long as the mouse button is pressed down. Fig. 2.10 illustrates this behavior that corresponds directly with the classical function of footnotes. The asterisk cursor is also derived from this metaphor. Replacement links reveal a more extensive description of the topic at the position of the hyperlink marker. The text gets stretched out. The reverse operation cuts down the text again.* * This description follows Jakob Nielsen [Nielsen 90, p. 91]. It is in conflict with the definition given by Jeff Conklin. He says that replacement links completely swap the content of the entire window while the standard case of reference jumps opens new windows (in Hypertext: An Introduction and Survey [Conklin 87, p. 32]).

Fig. 2.10 A typical Guide window. The mouse button is currently pressed to display a pop-up note.

Jakob Nielsen compares replacements with NLS’ feature to show and hide statements of a lower hierarchical level [Nielsen 90, p. 91]. And in fact Guide can mimic this behavior with replacement links. But the effect is more general and is a variation of Ted Nelson’s concept of Stretchtext. Nelson gives the following example [Nelson 74, p. dm 19]:

Stretchtext is a form of writing. It is read from a screen. The user controls it with throttles. It gets longer and shorter on demand.

would elastically expand to:

Stretchtext, a kind of hypertext is basically a form of writing closely related to other prose. It is read by a user or a student from a computer display screen. The user, or student, controls it, and causes it to change, with throttles connected to the computer. Stretchtext gets longer, by adding words and phrases, or shorter, by subtracting words and phrases, on demand.

Ted Nelson promotes Stretchtext as a form of hypertext with less chance to get lost.

à propos

![]() For a free PDF version of Vision and Reality of Hypertext and Graphical User Interfaces (122 pages), send an e-mail to:

For a free PDF version of Vision and Reality of Hypertext and Graphical User Interfaces (122 pages), send an e-mail to:

![]() mprove@acm.org I’ll usually respond within a day. [privacy policy]

mprove@acm.org I’ll usually respond within a day. [privacy policy]